Peace Guidebook Part 4: The Wordless World Principle

If you have not yet read the rest of the Peace Guidebook, I suggest you first read the introduction and other parts.

Part 4: The Wordless World Principle

We have gone from the brain to behavior and now lastly we will look at how language can affect peace in the mind, body and world. The knowledge for this part comes from the book Science and Sanity by Alfred Korzybski.

As I said in the previous part, the Anatomy of Peace is the one book I think everyone should read and can read. Science and Sanity on the other hand is the book I would say everyone should read, but I don't expect everyone will because it’s about 700 pages. It's very dense and it gets into very complicated things, but I'm going to break down my key take aways and outline my evolved understanding of General Semantics.

The author Alfred Korzybski was a Polish American mathematician who wanted to explain language with math, and he created the field known as General Semantics, which is the study of language through rationality, math and logic and how language affects sanity.

Since he published his work in the book Science and Sanity in 1933, other writers have picked up his work and also written about General Semantics in other books, but General Semantics is still not very well known.

I believe the principles of General Semantics are very important and with more awareness could lead to a revolution in thought.

The basic premise of the book is studying language through math, and Korzybski breaks down language into two forms of language. There's the language that's based in reality and the language that's based in abstraction.

He brings everything down scientifically to a nervous system level. In your body, your brain is attached to the nervous system, and Korzybski talks about how when you're using the right language, your nervous system becomes at peace. But if you are using the wrong kind of language, your nervous system becomes agitated.

Before we can figure out what is the right language or the wrong language though, we first have to ask the question: What is language?

Take special note of the word “abstract” at the end of the third definition of language and remember that for when we start breaking down language.

To understand language, Korzybski relates language to a map with this very important phrase:

As Korzybski says, “the map is not the territory. The only usefulness of the map depends on the similarities of the structure between the empirical world and the map.”

A map is a two dimensional representation of the world. We must not confuse the map with being the actual world we’re travelling in. It’s just a representation. And the more accurate the map the better we will be at getting to our destination.

Let’s say you're trying to travel somewhere with a map. The map is only useful if it helps you get to where you want to go. If you are on Vancouver Island, and you want to get from Nanaimo to Victoria, but instead you have a map of England, that map isn’t going to be very useful to you on Vancouver Island.

Or let's say you have a map of Vancouver Island, and someone has messed around with it and put Victoria up to the north, and Nanaimo further down south, and everything is rearranged. The map is not going to be useful. It's not going to help us.

Korzybski says it's the same thing with language. Language is either based on a correct representation of the world, or it's a misrepresentation. Language is either useful or it’s not.

So it’s really important to remember that the map is not the territory.

Then there's the next phrase which is: “The word is not the thing.”

The best argument I can make in terms of stressing that the word is not the thing is you just have to look at different languages.

Let's use a dog as an example. In English we would say the word “dog”. Everyone who speaks in English would all agree that a dog is a dog. But in French, we would say “chien", and in Spanish we would say “perro”. There are hundreds of languages with different words for the same thing. The fact that we can have all these different languages come up with a different word for the same thing, shows that the word is not itself the thing. It is just what we as people have agreed to call the thing.

I think Shakespeare said it the most eloquently. “What's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.”

If a group of people decided to call this flowery thing a blue buddy (we all could come to that decision together), then we'd be calling this a blue buddy, but calling it a blue buddy is not going to change the fact that it's not blue. It's red, and it might not be your buddy. It has thorns and it might prick you.

Changing the name of what the object is called, doesn't change the physical principles, the essence of what that thing is.

So what is language? If I were to define it very simply, language is an agreed upon symbolic code of communication. Also I believe that good communication leads to agreement.

You cannot have agreement without good communication, and good communication is based on an agreed upon symbolic code of communication. It's circular. You have to agree on the words before you can agree on anything else.

Now that we have an understanding of what language is we can break down the levels of language with the different levels of reality.

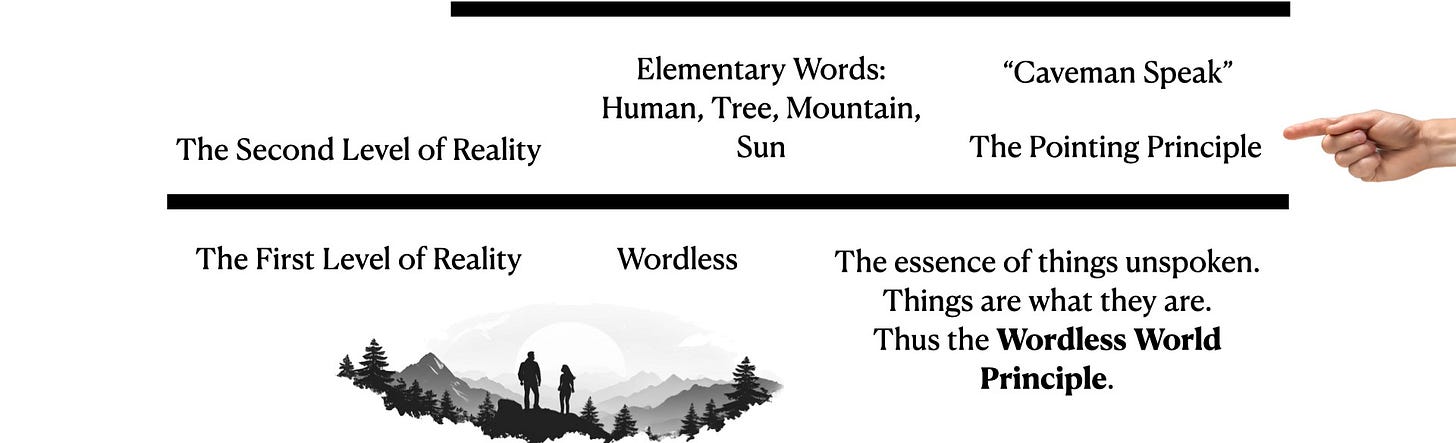

The first level of reality is wordless. There is no language. There are no words. Words are something we as humans have come up with and created. The world is really wordless. This is the most true level of reality.

Everything just is what it is. The essence of things are unspoken. Things simply are what they are.

The name I’ve personally come up with to call this basic understanding of the first level of reality is the “Wordless World Principle”.

The second level of reality is where you actually start implementing language, but it's very basic elementary language. It is language that a caveman can understand. It’s very simple. You can point to something, say what the thing is such as “rock”, “book”, “chair” and everyone can agree on it.

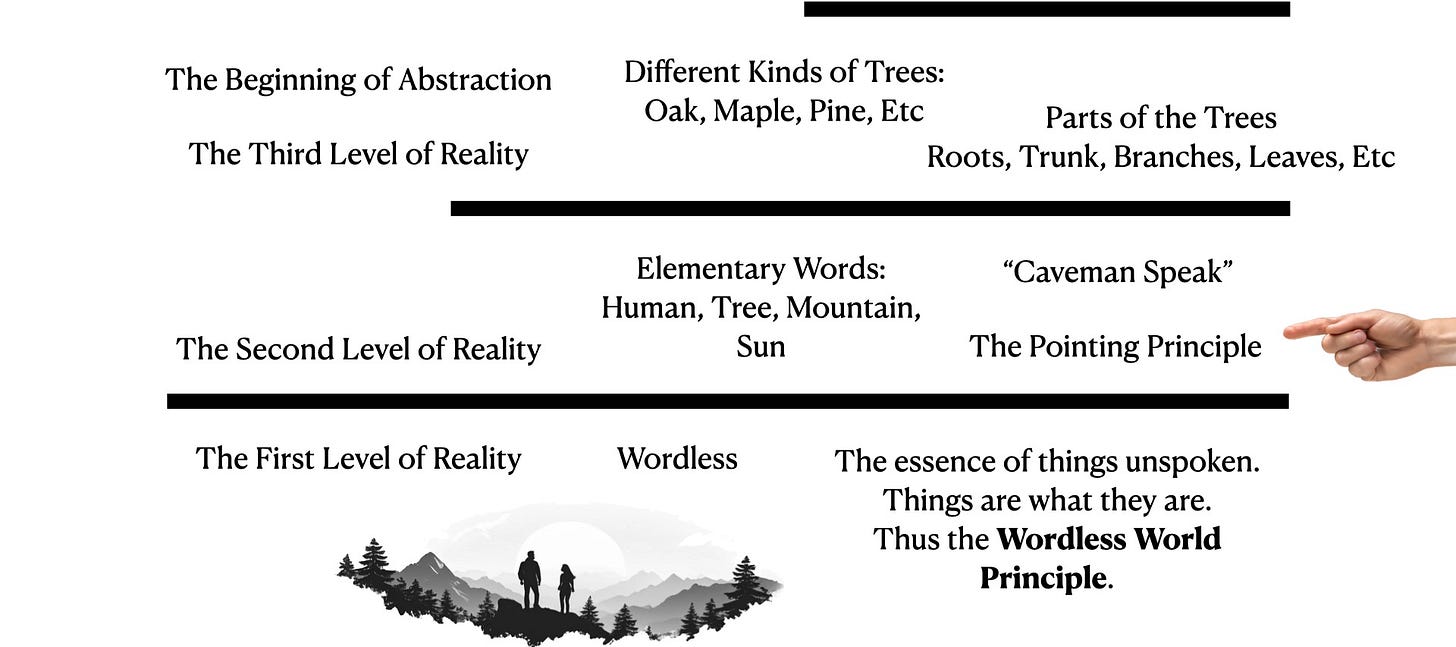

Then we go into the beginnings of the abstraction. This is the third level of reality and where things start to be abstracted.

For this level, I will use the example of a tree. We can all point to a tree and agree on what a tree is, but then there are also different types of trees. There are oak trees, there are maple trees, pine trees, etc. You can abstract things broadly into different species, and then you can also abstract into the micro where you can start abstracting the object into different parts. You can point to a tree and then you can point at the trunk of the tree, the roots of the tree, and the leaves.

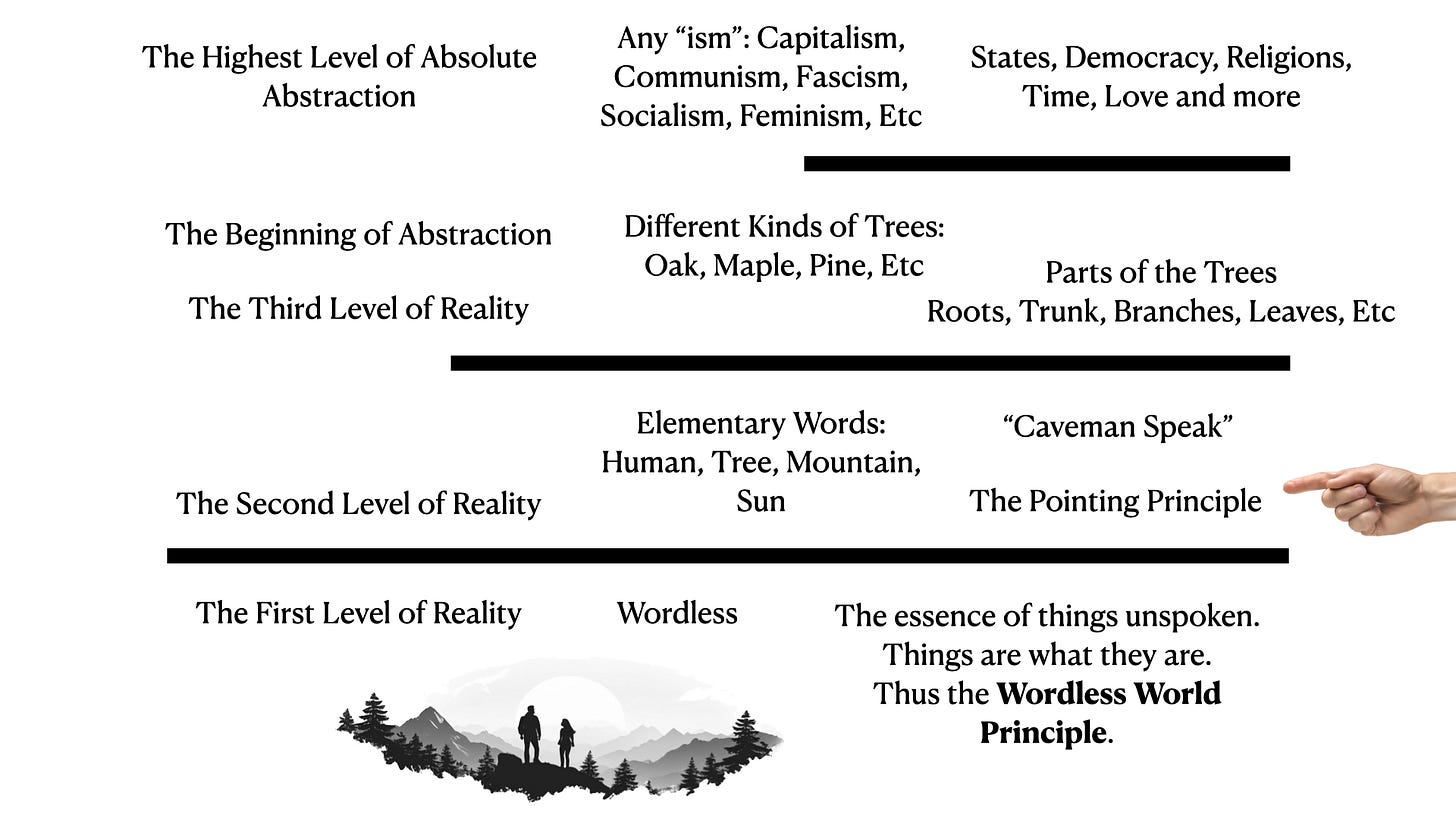

You can go to multiple different levels of abstraction, but I'm just gonna jump to the highest level of absolute abstraction, which is where words have no basis in the physical world.

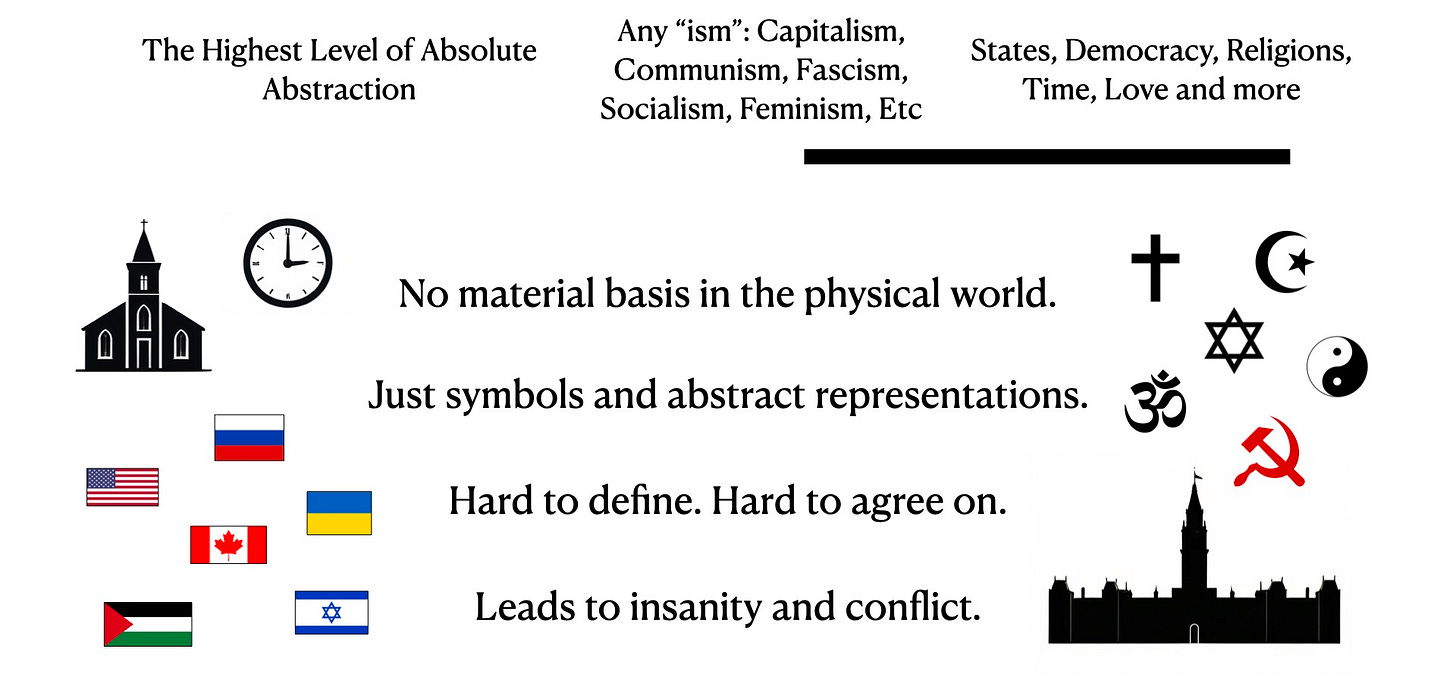

The words I really point out is any “ism” such as capitalism, socialism, communism, fascism, feminism, etc. Any sort of “ism” you can think of is not something that is actually based in the physical world. Other things we can talk about that are abstract are: states, countries, democracy, religions, time, and love. I’m going to add corporations to that list. There’s probably an endless list of all these things that are words that we have in our heads but you can't actually point at it in the real world.

There's no material basis in the physical world for these words. They're just symbols and abstract representations. Like a map. Using a country as an example, if you were to tell someone to point at Canada, first of all, I could go find a map and point to Canada on a map, but like we said earlier, the map is not the territory. Canada on the map is not the real Canada in the real world.

So if I were to ask you to point at Canada, you might point at the flag, but the flag is not Canada. The flag is just a representation of Canada. You might point at the parliament building, but that's not Canada as well. Canada and every country in the world is an abstract idea in our head that has a bunch of different symbols and abstract representation, but there's nothing concrete of what Canada or any country really is.

The same can be said with religions or ideologies. Using communism as an example, I can’t point at communism. I could point at the symbol of communism, the sickle and hammer, but that is not communism itself.

The key thing to take away from this is that these abstract words become very hard to define because you can't actually point at it, and that makes it very hard to agree on what these things actually are.

Unless you're talking to someone who has the same idea of what something is, it is going to be hard to agree on it. You have to first agree what the word means and it's very difficult if that thing is not based in the real world.

Going back to the book Science and Sanity, Korzybski’s major point is that when we live with our minds in this highest abstract level, where nothing is based in the physical reality, then that's where insanity is induced, and conflict arises in the world as a result from these abstract things.

One thing I will stress though is that just because we say that something is just a word with no physical essence, I'm not going to deny the existence of these things. As an example, I could drop a book on the floor and it's going to fall because there's this thing called gravity. I can't point to gravity, but there's the law of gravity that we understand and you can see the effects of it, but I can't point to gravity. So gravity is an abstract thing, but I'm not going to say that gravity doesn't exist. Maybe someday in the future, someone will come up with a better scientific theory that will explain why books fall on the floor, but right now gravity is our best theory.

It’s not a matter of denying the existence of abstract things, but it is important to acknowledge the limitations of understanding what these things are due to their abstract nature and how this can lead to conflict.

So when you're having an argument with someone about something abstract, at the very least you need to have a little bit of patience and compassion for the other person, because first of all we don't want to have a heart at war. We want a heart at peace. We want to see people as people.

And we have to just understand that while we might use the same words, our understanding of the abstract words might not be the same and this is limiting our ability to agree.

If we want to really have peace and sanity though, what we need to do is bring everything back down to the basic levels of reality and understand that words are not the thing. Understand this and you will become well grounded in a chaotic world full of absolute abstraction.

There’s a good quote from the book Language in Though and Action by S.I. Hayakawa in which he talks about General Semantics and this is what he said:

“Citizens of a modern society need therefore more than that ordinary common sense, which was defined by Stuart Chase, as that which tells you that the world is flat. They need to be systematically aware of the powers and limitations of symbols, especially words, if they are to be guarded against being driven into a complete bewilderment by the complexity of the semantic environment."

I don’t know about you, but I feel like there's a lot of bewilderment in the world right now, and that's why we have a lot of conflict.

Finally one more quote from Korzybski:

“The map is not the territory. The word is not the thing it describes. Whenever the map is confused with the territory, a semantic disturbance is set up in the organism. The disturbance continues until the limitations of the map is recognized.”

This is taking everything back to the basic level of reality that is aligned with your nervous system. To avoid semantic disturbances and achieve peace you need to use language that is in correct relation to the physical reality.

Taking all this and applying it to situations in the world, let's say you're having a conflict with someone, one of the key questions to ask yourself in those situations is first of all: do you have an accurate map? You should always be questioning your map because if you don't have an accurate map you may be suffering from a semantic error.

And then the other question is, does the person you're having a conflict with have an accurate map? Because if you have an accurate map but they don’t, then you won’t be able to have agreement. The person with an inaccurate map won’t be able to agree with you because their map is causing a semantic error.

Conflict will continue as long as people have inaccurate maps. If we all had an accurate map, then we would all have more peace.

This is the final Part of the Peace Guidebook. I will be releasing the Conclusion tomorrow.